Keali‘i Reichel: A Life in Song

- featured work

- Keali‘i Reichel: A Life in Song

Keali‘i Reichel: A Life in Song

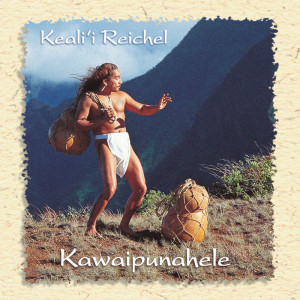

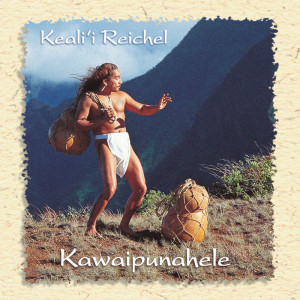

His career in music now bookended by his breakthrough debut album, Kawaipunahele, and what he says will be his last album, the recently released Kawaiokalena, the lauded musician and kumu hula reflects on the past 20 years of his life, love, family and musical inspiration via 12 songs.

Foreword: Tuesday in Pi‘iholo with Keali‘i

I’ve long wanted to ask Keali‘i Reichel to work with me on a feature like this issue’s “A Life in Song.”

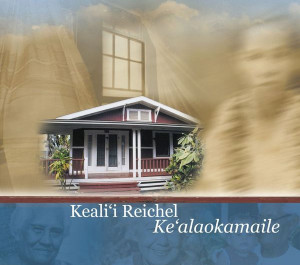

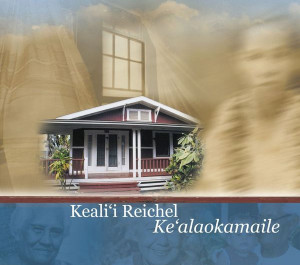

The multiple Nā Hōkū Hanohano Hawai‘i music award winning musician and Merrie Monarch Festival-winning kumu hula is one of the most iconic and influential individuals of modern Hawaiian music and culture, sure. But he’s also a fascinating guy to sit down with for a few hours and talk story. We’d spoken a couple of times before—the most memorable of these chats happening a decade ago when his 2003 album, Ke‘alaokamaile, was nominated for the first Best Hawaiian Music Album Grammy award.

He spoke then about the many kūpuna (grandparents and family elders) that had inspired much of Ke‘alaokamaile and shaped his view of the world. In particular, his grandmother, Kamaile Puhi Kane. His memories were rich, detailed, vivid, humorous, occasionally sad, and heavy with abundant love and respect for his subjects. I felt honored hearing the stories straight from the source.

So when I found out last summer that Reichel was recording his first album since Ke‘alaokaimaile—the recently released Kawaiokalena—I figured it was a good time to catch up and, maybe, hear a few more stories. Stories spanning the 20 years of his life and career since his breakthrough debut album, 1994’s Kawaipunahele.

And so I contacted Reichel with my idea: Select a dozen or so songs from your music career that personally mean the most to you, then sit down with me and share stories of their creation, the inspiration behind them and what was going on in your life when you recorded them. They didn’t have to be his best-known songs, I told him, just the ones he would put on a playlist of songs that told the story of his life.

Though, these days, Reichel only very rarely agrees to do interviews, he said “Yes” immediately to my request and was gracious, loquacious and just plain good fun when we eventually met at the Upcountry Maui home he shares with his husband and longtime inspiration for much of his music, Fred “Punahele” Krauss. I had an exceptional Tuesday afternoon with Reichel reminiscing his life in song, and I think he did, too.

I hope you enjoy the feature as much as I did putting it together.

The multiple Nā Hōkū Hanohano Hawai‘i music award winning musician and Merrie Monarch Festival-winning kumu hula is one of the most iconic and influential individuals of modern Hawaiian music and culture, sure. But he’s also a fascinating guy to sit down with for a few hours and talk story. We’d spoken a couple of times before—the most memorable of these chats happening a decade ago when his 2003 album, Ke‘alaokamaile, was nominated for the first Best Hawaiian Music Album Grammy award.

He spoke then about the many kūpuna (grandparents and family elders) that had inspired much of Ke‘alaokamaile and shaped his view of the world. In particular, his grandmother, Kamaile Puhi Kane. His memories were rich, detailed, vivid, humorous, occasionally sad, and heavy with abundant love and respect for his subjects. I felt honored hearing the stories straight from the source.

So when I found out last summer that Reichel was recording his first album since Ke‘alaokaimaile—the recently released Kawaiokalena—I figured it was a good time to catch up and, maybe, hear a few more stories. Stories spanning the 20 years of his life and career since his breakthrough debut album, 1994’s Kawaipunahele.

And so I contacted Reichel with my idea: Select a dozen or so songs from your music career that personally mean the most to you, then sit down with me and share stories of their creation, the inspiration behind them and what was going on in your life when you recorded them. They didn’t have to be his best-known songs, I told him, just the ones he would put on a playlist of songs that told the story of his life.

Though, these days, Reichel only very rarely agrees to do interviews, he said “Yes” immediately to my request and was gracious, loquacious and just plain good fun when we eventually met at the Upcountry Maui home he shares with his husband and longtime inspiration for much of his music, Fred “Punahele” Krauss. I had an exceptional Tuesday afternoon with Reichel reminiscing his life in song, and I think he did, too.

I hope you enjoy the feature as much as I did putting it together.

Back then, people used to make mix tapes on cassette. [Puna and I] were apart. And I had to go to Hāna to do something. So Puna made me a mix tape. And he put all of these heartbreak-type rock and roll, country, Hawaiian and all kine songs on the tape for my drive. I guess he just wanted to dig in the knife a little bit more [laughs]. I’d already written [the song] “Kawaipunahele.” So everything was still kind of painful, and he was still mad. One of the songs was the Ka‘au Crater Boys’ “Are You Missing Me.” Had some Mariah Carey. Those kinds of songs.

But he titled the cassette, E Ho‘i I Ka Pili, [which] means “to return to the relationship.” That was his subtle way of leaving the door open. And I really liked that phrase. And so, this whole song was built on that phrase that he put on the mix tape to dig in the knife [laughs hard]. Nobody knows that. Now you do.

Back then, people used to make mix tapes on cassette. [Puna and I] were apart. And I had to go to Hāna to do something. So Puna made me a mix tape. And he put all of these heartbreak-type rock and roll, country, Hawaiian and all kine songs on the tape for my drive. I guess he just wanted to dig in the knife a little bit more [laughs]. I’d already written [the song] “Kawaipunahele.” So everything was still kind of painful, and he was still mad. One of the songs was the Ka‘au Crater Boys’ “Are You Missing Me.” Had some Mariah Carey. Those kinds of songs.

But he titled the cassette, E Ho‘i I Ka Pili, [which] means “to return to the relationship.” That was his subtle way of leaving the door open. And I really liked that phrase. And so, this whole song was built on that phrase that he put on the mix tape to dig in the knife [laughs hard]. Nobody knows that. Now you do.

We were in the studio working on the second album [Lei Hali‘a]. It was about 11 or 12 at night. I was sitting on a bench outside the studio, taking a break from recording, and I remembered, “Ay! [Puna’s] birthday is coming up and I really should write a song.” For some strange reason, the opening of [the Jackson 5’s] “I’ll Be There” came into my head. I lifted the opening [of the song] from that. The whole song, structurally, is revolved around it. I wanted to remind him, through the lyric, that, even though we’d been together for a long time, [he was] still the same to me. That living with [him was] very, very calm. It’s the calming presence in my life. Pua mae ‘ole means “the flower that never fades.” When you’re in a relationship that has weathered a lot of storms, that person doesn’t change. They still look handsome to you, no matter what. I remember sitting on the bench, going through some of the lyric and grabbing my guitar. The whole mele (song) was pretty much written while I was taking that 45-minute break. [Lei Hali‘a] was a hard [album] to do. It was hard because of the expectations. Now everybody was looking. Trying not to buckle under that pressure is an immense thing. But I had to get to the point where I just did it and hoped for the best. But it wasn’t as easy a birth as the first [album]. The first one we nevah know nothing. Now we were aware. It was a tough hurdle to get over.

We were in the studio working on the second album [Lei Hali‘a]. It was about 11 or 12 at night. I was sitting on a bench outside the studio, taking a break from recording, and I remembered, “Ay! [Puna’s] birthday is coming up and I really should write a song.” For some strange reason, the opening of [the Jackson 5’s] “I’ll Be There” came into my head. I lifted the opening [of the song] from that. The whole song, structurally, is revolved around it. I wanted to remind him, through the lyric, that, even though we’d been together for a long time, [he was] still the same to me. That living with [him was] very, very calm. It’s the calming presence in my life. Pua mae ‘ole means “the flower that never fades.” When you’re in a relationship that has weathered a lot of storms, that person doesn’t change. They still look handsome to you, no matter what. I remember sitting on the bench, going through some of the lyric and grabbing my guitar. The whole mele (song) was pretty much written while I was taking that 45-minute break. [Lei Hali‘a] was a hard [album] to do. It was hard because of the expectations. Now everybody was looking. Trying not to buckle under that pressure is an immense thing. But I had to get to the point where I just did it and hoped for the best. But it wasn’t as easy a birth as the first [album]. The first one we nevah know nothing. Now we were aware. It was a tough hurdle to get over.

“E Ō Mai” was actually written as a homework assignment. I was flying into Honolulu every week to take a class from my friend [Hawaiian language educator and composer] Puakea Nogelmeier. He was teaching a course on haku mele (song and chant composition). It was great. It was a small class. We had to go through all of the exercises of traditional composition, study the motifs and things like that. And we all knew that, at the end of the semester, we would have to come up with a chant or song as a final project and present it to the class. In this type of lifestyle, because you don’t have a 9-to-5 job, sometimes you lose track of time. Oftentimes, I don’t even know what date it is. I always have to look on my phone or things like that. So, one time, I was on the plane, relaxing, the plane took off and, all of a sudden, I was, like, “Ay, I think this is the last day of class.” And I had nothing. I took my napkin—me and napkins—and I asked the flight attendant for a pen. Fortunately, I already had this tune in my head—the “E Ō Mai” tune. [In class] we had been talking about utilizing natural elements in poetry. I decided to use water—the uses of water, and water in the context of sex and making love. You gotta have water to survive. And you have to have making love to be human. That’s kind of what the song talks about. By the time I landed in Honolulu the whole [song] was pau (finished). All on a 20-minute flight, because I HAD to. And very little of it was corrected or adjusted. When I sang it in front of the class, everybody was kind of, like, “Wow!” I was kind of, “Wow!” too. I got an A.

“E Ō Mai” was actually written as a homework assignment. I was flying into Honolulu every week to take a class from my friend [Hawaiian language educator and composer] Puakea Nogelmeier. He was teaching a course on haku mele (song and chant composition). It was great. It was a small class. We had to go through all of the exercises of traditional composition, study the motifs and things like that. And we all knew that, at the end of the semester, we would have to come up with a chant or song as a final project and present it to the class. In this type of lifestyle, because you don’t have a 9-to-5 job, sometimes you lose track of time. Oftentimes, I don’t even know what date it is. I always have to look on my phone or things like that. So, one time, I was on the plane, relaxing, the plane took off and, all of a sudden, I was, like, “Ay, I think this is the last day of class.” And I had nothing. I took my napkin—me and napkins—and I asked the flight attendant for a pen. Fortunately, I already had this tune in my head—the “E Ō Mai” tune. [In class] we had been talking about utilizing natural elements in poetry. I decided to use water—the uses of water, and water in the context of sex and making love. You gotta have water to survive. And you have to have making love to be human. That’s kind of what the song talks about. By the time I landed in Honolulu the whole [song] was pau (finished). All on a 20-minute flight, because I HAD to. And very little of it was corrected or adjusted. When I sang it in front of the class, everybody was kind of, like, “Wow!” I was kind of, “Wow!” too. I got an A.

I was still living in Wailuku. According to the writings of Inez Ashdown, who was Maui County’s historian emeritus [at Bailey House Museum], the two mountains that make up both sides of [nearby] ‘Iao Valley [are] Maunaleo and Maunakāne. I really liked the term Maunaleo (which means “the mountain’s voice”). I threw down some lines for Puakea and I said, “This is the tune. I’m missing a few lines in here, and I can’t make it work rhythmically.” I told him that the imagery that I had [in the words] was my mother. That this mountain is there. It stands like a sentinel. And no matter what’s come its way—fire, flood, storms—it’s still there. My mother is like that. In my immediate family she’s the rock and the scary one. Puakea came back and filled in some of the blanks. We adjusted some of the rhythm and some of the imagery. Like the song version of “He Lei No Kamaile” for my grandmother, [“Maunaleo”] wasn’t born right away. We had to sit and intellectually and culturally look at the imagery and say, “This is what we want to say,” and ask, “What if we use this word instead of that word?” There was a lot of bandying about.

I was still living in Wailuku. According to the writings of Inez Ashdown, who was Maui County’s historian emeritus [at Bailey House Museum], the two mountains that make up both sides of [nearby] ‘Iao Valley [are] Maunaleo and Maunakāne. I really liked the term Maunaleo (which means “the mountain’s voice”). I threw down some lines for Puakea and I said, “This is the tune. I’m missing a few lines in here, and I can’t make it work rhythmically.” I told him that the imagery that I had [in the words] was my mother. That this mountain is there. It stands like a sentinel. And no matter what’s come its way—fire, flood, storms—it’s still there. My mother is like that. In my immediate family she’s the rock and the scary one. Puakea came back and filled in some of the blanks. We adjusted some of the rhythm and some of the imagery. Like the song version of “He Lei No Kamaile” for my grandmother, [“Maunaleo”] wasn’t born right away. We had to sit and intellectually and culturally look at the imagery and say, “This is what we want to say,” and ask, “What if we use this word instead of that word?” There was a lot of bandying about.

The song is about my grandmother’s house in Pā‘ia. It’s one of those old plantation-style homes. It’s right on the beach, which is unusual [for the area] nowadays. The house actually belonged to her aunty. My grandmother had been adopted into that family [but was] related by blood. She grew up here on Maui, but her roots are in Kohala. Her sisters and brothers were all raised in Kohala. The house became central for our entire family. Summertime we would have huge family gatherings. Tents everywhere. Fishing every day. Swimming every day. And music. When [her] aunty died, my grandmother moved into the house and lived there until she died. My mother’s sister continued to live there and we would go often. But, after a year, my aunty decided that she didn’t want to live there anymore. That was like a second death to us, because that hale (house) was our connection. It was our grounding. So I decided to write about all of the things I heard, saw and felt. The coconut trees—there’s a certain kind of sound that occurs. The sea spray. The sound of the ti leaves in the wind right outside the windows, because the windows were low. I wanted to document in song and imagery all of the stuff that me and the older cousins remembered. Some of the generation below us didn’t know my grandmother or had never met her. And it was important for me to do [the song] as a record, first and foremost, for the family. The house is still in the family. The energy is a little bit different, because it’s a different branch. We still have family gatherings, but not as many as before. And I sometimes take my hālau there so they can experience what I’ve experienced. A lot of the hālau chants that we do talk about that house. There’s nothing quite like using the environment as a teaching tool, especially when it comes to chant. I make them walk the yard and listen. I make them go down to the ocean and feel the temperature because the water and sand is different from the rest of the island. Hitting all of their senses and utilizing chants from this album, or chants within hālau that nobody else knows except hālau, is important.

The song is about my grandmother’s house in Pā‘ia. It’s one of those old plantation-style homes. It’s right on the beach, which is unusual [for the area] nowadays. The house actually belonged to her aunty. My grandmother had been adopted into that family [but was] related by blood. She grew up here on Maui, but her roots are in Kohala. Her sisters and brothers were all raised in Kohala. The house became central for our entire family. Summertime we would have huge family gatherings. Tents everywhere. Fishing every day. Swimming every day. And music. When [her] aunty died, my grandmother moved into the house and lived there until she died. My mother’s sister continued to live there and we would go often. But, after a year, my aunty decided that she didn’t want to live there anymore. That was like a second death to us, because that hale (house) was our connection. It was our grounding. So I decided to write about all of the things I heard, saw and felt. The coconut trees—there’s a certain kind of sound that occurs. The sea spray. The sound of the ti leaves in the wind right outside the windows, because the windows were low. I wanted to document in song and imagery all of the stuff that me and the older cousins remembered. Some of the generation below us didn’t know my grandmother or had never met her. And it was important for me to do [the song] as a record, first and foremost, for the family. The house is still in the family. The energy is a little bit different, because it’s a different branch. We still have family gatherings, but not as many as before. And I sometimes take my hālau there so they can experience what I’ve experienced. A lot of the hālau chants that we do talk about that house. There’s nothing quite like using the environment as a teaching tool, especially when it comes to chant. I make them walk the yard and listen. I make them go down to the ocean and feel the temperature because the water and sand is different from the rest of the island. Hitting all of their senses and utilizing chants from this album, or chants within hālau that nobody else knows except hālau, is important.

This is my first song for the area I live in now [Pi‘iholo]. I think the song came first, before we even thought about the album. That’s when everything began to click. On the surface, it was about the place. But, in the chant I wrote for [Puna’s] 50th birthday, I gave him a new name, another name: Kawaiokalena. Kalena is the name of a series of ponds right down the street from here. They were famous in ancient times for whenever ali‘i (royalty) would come from other islands. When they traveled on Maui, they would inevitably stop there. So those are the royal ponds. There’s a small heiau (temple) next to one of the ponds, which tells you of its importance, culturally. When I gave [Puna] his name and his chant, I called it “the water of Kalena” [the English translation of kawaiokalena].” Just like Kawaipunahele. To me, it’s a water name. It also fit as a bookend. Everything [for the album] came very quickly after that. And so, really, this song and the chant talk about how we were on the ridge here and how the clouds nestled. Sometimes you can’t even see out this window. You’re in the thick of clouds. They roll in. It’s weird and kind of scary, actually. And if you open up all the windows it comes in. It’s very, very elemental up here. And so [the song] talks about this place. What I hope to do, as it has been with a lot of songs and chants and stuff, is to reintroduce people to a place again. A lot of my songs on the first albums—through turns of phrase, through poetry, through chant—reintroduced people to Wailuku and reminded them of all the things that made Wailuku famous. I hope some of what’s on this album does the same thing for the Pi‘iholo area.

This is my first song for the area I live in now [Pi‘iholo]. I think the song came first, before we even thought about the album. That’s when everything began to click. On the surface, it was about the place. But, in the chant I wrote for [Puna’s] 50th birthday, I gave him a new name, another name: Kawaiokalena. Kalena is the name of a series of ponds right down the street from here. They were famous in ancient times for whenever ali‘i (royalty) would come from other islands. When they traveled on Maui, they would inevitably stop there. So those are the royal ponds. There’s a small heiau (temple) next to one of the ponds, which tells you of its importance, culturally. When I gave [Puna] his name and his chant, I called it “the water of Kalena” [the English translation of kawaiokalena].” Just like Kawaipunahele. To me, it’s a water name. It also fit as a bookend. Everything [for the album] came very quickly after that. And so, really, this song and the chant talk about how we were on the ridge here and how the clouds nestled. Sometimes you can’t even see out this window. You’re in the thick of clouds. They roll in. It’s weird and kind of scary, actually. And if you open up all the windows it comes in. It’s very, very elemental up here. And so [the song] talks about this place. What I hope to do, as it has been with a lot of songs and chants and stuff, is to reintroduce people to a place again. A lot of my songs on the first albums—through turns of phrase, through poetry, through chant—reintroduced people to Wailuku and reminded them of all the things that made Wailuku famous. I hope some of what’s on this album does the same thing for the Pi‘iholo area.

Photo: Uilani Friedman, courtesy of Keali‘I Reichel

Keali‘i Reichel: A Life in Song

It’s incomprehensible now to imagine absolutely no one wanting to sign Keali‘i Reichel to a recording contract or put him in a studio. But, once upon an apparently unenlightened time in artist acquisition in the Hawai‘i music industry, that was the case.

In 1993, armed with a cassette tape of songs he’d written and home-recorded, and hoping to record a proper album, Reichel—and his then-partner, now-husband Fred “Punahele” Krauss—made the rounds of several local record labels. Then an up-and-coming kumu hula (hula teacher), his fulltime job director of the Bailey House Museum on Maui, Reichel was turned away by every one of them. “They literally laughed us out of their offices. Literally. Almost all of them,” he says. Undaunted, the pair took another path, scanning the liner notes of their favorite Hawai‘i music albums in search of someone they might approach to record Reichel. A common name threading through albums they liked from Olomana, the Brothers Cazimero and the Makaha Sons of Ni‘ihau was recording engineer Jim Linkner. Friend and Makaha Son Louis “Moon” Kauakahi set up a lunch meeting between Reichel, Krauss and Linkner. “And so Puna and I flew to Honolulu,” says Reichel. (“Puna” is short for “Punahele,” one of many names Reichel has given Krauss in song and chant over the years.) “We were so poor, we couldn’t rent a car to meet him. So we caught TheBus from the airport.” Based mostly on how well they clicked talking story—“He didn’t even hear me sing,” says Reichel—Linkner agreed to record him. Reichel and Krauss then set out on the lengthy, considerable task of raising money for the recording session. Recalls Reichel, “We raised money through our halau (hula troupe). We sold cookies and taro bread to fund part of it. Puna’s mom gave us a loan. And we put together just enough money to do about three weeks of recording.” They recorded the album quickly—some of it in a recording studio, but most of it in the living room of a friend’s house—and, at Linkner’s suggestion, formed their own label to release it. The album’s title was taken from the first song Reichel wrote for it. The first song he’d ever written, before he’d even conceived of it ending up on an album or that he would have career as a musician. A song that, as with every song he’d penned for the album, was specifically about Krauss: “Kawaipunahele.” “Nobody knew that Kawaipunahele was Puna,” says Reichel. “At the time, we were very, very cognizant of being genderless. I didn’t want to be known as ‘that gay Hawaiian singer.’ I just wanted to be known as a Hawaiian singer.” Reichel shares this story in the home he and Krauss have shared for the past six years in the cool, rain-kissed, forested highlands of upper Pi‘iholo on Maui. They have been together for three decades and Reichel calls Krauss the inspiration for nearly all of the songs he’s written over his two-decade music career. Truth be told, Reichel’s breakthrough album, Kawaipunahele, might not have happened at all had Reichel and Krauss not briefly broken up 21 years ago. “That was the catalyst. I was in that phase of my life after about seven or eight years [together] where I was kind of, like, ‘I love you. But I’m not in love with you,’” remembers Reichel, now 53, of his 31-year-old self. “And so we split up. Then after about a month, I changed my mind.” Reichel lets out a throaty laugh. “So I was, like, ‘Come back!’ And he was, like, ‘Uh-uh. No ways.’” Away on a trip to Hawai‘i Island, post-breakup and heartbroken, words and music entered Reichel’s head. He’d written spoken chants before, but this was new: a song. He found a pen and wrote down the words as fast as he could on a Burger King napkin, the only paper available. Writing the song made him feel better. But when Reichel returned to Maui and presented the song to Krauss, he found his ex unmoved. So Reichel wrote more songs. Songs based on the breakup. Songs based on trying to get back together. Songs filled with regret. He showed them all to Krauss. “We were still friends. And Puna said, ‘You really should think about recording these,’” says Reichel. “In my mind, I was thinking, ‘If there’s going to be a chance in this to work with you and just be around you then I’ll do it.’ I never told him that. But that was my way of staying connected.” Released in 1994, Kawaipunahele proved an instant smash on Hawaiian music radio and a bestseller in Hawai‘i record stores, launching a long and successful music career Reichel had never seen coming. On the album’s release date, a year after their initial breakup, Reichel and Krauss moved back in together. Six albums, dozens of music awards, hundreds of worldwide concerts and one Grammy Award nomination later, they are still together, still inspiring each other. There are no awards or artifacts in Reichel’s living room marking the myriad accomplishments of his careers in music or as a kumu hula. Like the rest of the woodsy home, the space is cozy, very much lived in—though neatly so—and filled with the varied interests of his and Krauss’s lives. Music doesn’t occupy as large a portion of Reichel’s daily life as other pursuits do, and that’s the way he prefers it. He travels often, teaches hula and can get lost for hours in the art of Hawaiian knotting and net making. He shows me his latest works, in various stages of completion, spread throughout the living room. “And this yard takes a lot of time, too,” he says, chuckling, while pointing out the living room window toward ‘ōhi‘a and koa. The native trees once made up much of the upper Pi‘iholo canopy before tall, dominating eucalyptus was planted by foresters. “I’m trying to reestablish a little place that was original to this place.” Last fall, Reichel recorded and released his first album in 11 years, Kawaiokalena. Its subject matter is largely reflective of those interceding years, touching on his and Krauss’s move from their longtime home in Wailuku to Pi‘iholo, his travels, the loss of friends and mentors, and, of course, Krauss. Kawaiokalena is also, Reichel insists, his final music album. “Everything comes to an end. And I like having that control,” says Reichel. “You should never say never. But if you think how long it was between albums, I don’t know that I can do another album when I’m 62 or 63. “Maybe I could. Life may have changed by then. But in my mind this is a bookend. A really nice bookend to a charmed and very blessed career.” Over three hours, as chilly Haleakalā winds blew through the rafters, forest birds chattered in the nearby eucalyptus forest and we devoured takeout laulau and garlic chicken Krauss had bought for lunch, Reichel reminisced about the stories and inspiration behind 12 songs from his music career that best echoed his life and still mean the most to him.“KAWAIPUNAHELE” from Kawaipunahele (1994)

The song is, basically, begging [laughs]. It’s a begging song. I’m a science fiction/fantasy buff. Big time. I liken [the song] to a powerful spell to entice the lover to come back. If you look at the words, that’s what that is. E huli ho‘i kāua [means] “Let’s go back. Let’s turn back and do this again.” Little did I know then that you can never go back. You just have to rediscover a new norm. But this song was my way of expressing the need to be with [Puna]. And, in retrospect, I think the spell worked [laughs]. If you look at the lyrics from the first album carefully, all of the songs are like that. They’re just approached in a different way, with slightly different phrasing. “Kawaipunahele,” to me, was the catalyst. The opening. It was my very first song ever. It was the song that opened that particular door of creativity.“E HO‘I I KA PILI” from Kawaipunahele (1994)

Back then, people used to make mix tapes on cassette. [Puna and I] were apart. And I had to go to Hāna to do something. So Puna made me a mix tape. And he put all of these heartbreak-type rock and roll, country, Hawaiian and all kine songs on the tape for my drive. I guess he just wanted to dig in the knife a little bit more [laughs]. I’d already written [the song] “Kawaipunahele.” So everything was still kind of painful, and he was still mad. One of the songs was the Ka‘au Crater Boys’ “Are You Missing Me.” Had some Mariah Carey. Those kinds of songs.

But he titled the cassette, E Ho‘i I Ka Pili, [which] means “to return to the relationship.” That was his subtle way of leaving the door open. And I really liked that phrase. And so, this whole song was built on that phrase that he put on the mix tape to dig in the knife [laughs hard]. Nobody knows that. Now you do.

Back then, people used to make mix tapes on cassette. [Puna and I] were apart. And I had to go to Hāna to do something. So Puna made me a mix tape. And he put all of these heartbreak-type rock and roll, country, Hawaiian and all kine songs on the tape for my drive. I guess he just wanted to dig in the knife a little bit more [laughs]. I’d already written [the song] “Kawaipunahele.” So everything was still kind of painful, and he was still mad. One of the songs was the Ka‘au Crater Boys’ “Are You Missing Me.” Had some Mariah Carey. Those kinds of songs.

But he titled the cassette, E Ho‘i I Ka Pili, [which] means “to return to the relationship.” That was his subtle way of leaving the door open. And I really liked that phrase. And so, this whole song was built on that phrase that he put on the mix tape to dig in the knife [laughs hard]. Nobody knows that. Now you do.“KAUANOEANUHEA” from Kawaipunahele (1994)

“Kauanoeanuhea” was just one of those ways of expressing a searching. A searching for your other half. Kauanoeanuhea is really a person’s name, like Kawaipunahele. In Hawaiian poetry, names are sometimes given with the giving of a song. And Kauanoeanuhea is [Puna’s] name—one of his many Hawaiian names now. It’s [a] cold, crispy mist that’s kind of fragrant. Puna had moved out and I was living at Bailey House Museum, right at the edge of ‘Īao [Valley]. It was one of those dreary days that didn’t help with my emotions. It was rainy. It was chilly. The clouds were really, really low and so all of this mist kept going in and out of the area. The mist would come down and it would go up. And as I looked at it I thought, “Oh, that’s kind of like love.” It was like him, the other half—in [my] life and out of [my] life. That’s where the first line comes from. “Auhea wale ana ‘oe e Kauanoeanuhea?” “Where are you, oh, fragrant mist?” I look for you. I kind of know where you are. But I can’t obtain you. Like mist, you can’t really grab it. You just have to sit there and let it come to you. It was a lesson in patience. This was my way of expressing that particular feeling on that day and making the comparison of this person in my life to the mist.“KU‘U PUA MAE ‘OLE” from Lei Hali‘a (1995)

We were in the studio working on the second album [Lei Hali‘a]. It was about 11 or 12 at night. I was sitting on a bench outside the studio, taking a break from recording, and I remembered, “Ay! [Puna’s] birthday is coming up and I really should write a song.” For some strange reason, the opening of [the Jackson 5’s] “I’ll Be There” came into my head. I lifted the opening [of the song] from that. The whole song, structurally, is revolved around it. I wanted to remind him, through the lyric, that, even though we’d been together for a long time, [he was] still the same to me. That living with [him was] very, very calm. It’s the calming presence in my life. Pua mae ‘ole means “the flower that never fades.” When you’re in a relationship that has weathered a lot of storms, that person doesn’t change. They still look handsome to you, no matter what. I remember sitting on the bench, going through some of the lyric and grabbing my guitar. The whole mele (song) was pretty much written while I was taking that 45-minute break. [Lei Hali‘a] was a hard [album] to do. It was hard because of the expectations. Now everybody was looking. Trying not to buckle under that pressure is an immense thing. But I had to get to the point where I just did it and hoped for the best. But it wasn’t as easy a birth as the first [album]. The first one we nevah know nothing. Now we were aware. It was a tough hurdle to get over.

We were in the studio working on the second album [Lei Hali‘a]. It was about 11 or 12 at night. I was sitting on a bench outside the studio, taking a break from recording, and I remembered, “Ay! [Puna’s] birthday is coming up and I really should write a song.” For some strange reason, the opening of [the Jackson 5’s] “I’ll Be There” came into my head. I lifted the opening [of the song] from that. The whole song, structurally, is revolved around it. I wanted to remind him, through the lyric, that, even though we’d been together for a long time, [he was] still the same to me. That living with [him was] very, very calm. It’s the calming presence in my life. Pua mae ‘ole means “the flower that never fades.” When you’re in a relationship that has weathered a lot of storms, that person doesn’t change. They still look handsome to you, no matter what. I remember sitting on the bench, going through some of the lyric and grabbing my guitar. The whole mele (song) was pretty much written while I was taking that 45-minute break. [Lei Hali‘a] was a hard [album] to do. It was hard because of the expectations. Now everybody was looking. Trying not to buckle under that pressure is an immense thing. But I had to get to the point where I just did it and hoped for the best. But it wasn’t as easy a birth as the first [album]. The first one we nevah know nothing. Now we were aware. It was a tough hurdle to get over.“E Ō MAI” from E Ō Mai (1997)

“E Ō Mai” was actually written as a homework assignment. I was flying into Honolulu every week to take a class from my friend [Hawaiian language educator and composer] Puakea Nogelmeier. He was teaching a course on haku mele (song and chant composition). It was great. It was a small class. We had to go through all of the exercises of traditional composition, study the motifs and things like that. And we all knew that, at the end of the semester, we would have to come up with a chant or song as a final project and present it to the class. In this type of lifestyle, because you don’t have a 9-to-5 job, sometimes you lose track of time. Oftentimes, I don’t even know what date it is. I always have to look on my phone or things like that. So, one time, I was on the plane, relaxing, the plane took off and, all of a sudden, I was, like, “Ay, I think this is the last day of class.” And I had nothing. I took my napkin—me and napkins—and I asked the flight attendant for a pen. Fortunately, I already had this tune in my head—the “E Ō Mai” tune. [In class] we had been talking about utilizing natural elements in poetry. I decided to use water—the uses of water, and water in the context of sex and making love. You gotta have water to survive. And you have to have making love to be human. That’s kind of what the song talks about. By the time I landed in Honolulu the whole [song] was pau (finished). All on a 20-minute flight, because I HAD to. And very little of it was corrected or adjusted. When I sang it in front of the class, everybody was kind of, like, “Wow!” I was kind of, “Wow!” too. I got an A.

“E Ō Mai” was actually written as a homework assignment. I was flying into Honolulu every week to take a class from my friend [Hawaiian language educator and composer] Puakea Nogelmeier. He was teaching a course on haku mele (song and chant composition). It was great. It was a small class. We had to go through all of the exercises of traditional composition, study the motifs and things like that. And we all knew that, at the end of the semester, we would have to come up with a chant or song as a final project and present it to the class. In this type of lifestyle, because you don’t have a 9-to-5 job, sometimes you lose track of time. Oftentimes, I don’t even know what date it is. I always have to look on my phone or things like that. So, one time, I was on the plane, relaxing, the plane took off and, all of a sudden, I was, like, “Ay, I think this is the last day of class.” And I had nothing. I took my napkin—me and napkins—and I asked the flight attendant for a pen. Fortunately, I already had this tune in my head—the “E Ō Mai” tune. [In class] we had been talking about utilizing natural elements in poetry. I decided to use water—the uses of water, and water in the context of sex and making love. You gotta have water to survive. And you have to have making love to be human. That’s kind of what the song talks about. By the time I landed in Honolulu the whole [song] was pau (finished). All on a 20-minute flight, because I HAD to. And very little of it was corrected or adjusted. When I sang it in front of the class, everybody was kind of, like, “Wow!” I was kind of, “Wow!” too. I got an A.“HE LEI NO KAMAILE” Chant from E Ō Mai (1997). Song from Ke‘alaokamaile (2003)

The chant came first. It was written for my grandmother and was presented to her at the King Kamehameha Hula Competition at the [Neal] Blaisdell [Arena on O‘ahu]. My grandmother was such an influence in my life and in my family’s life. We were very lucky that she lived into her 80s. I knew my grandmother all of my life until 2000, when she passed. I was already writing chants before I started writing songs. We decided that I needed to, through example, create an honorific genealogy chant for my grandmother while she was still alive. [“He Lei No Kamaile”] talks about her roots in Kohala in the first verse. Then she moved to Maui, had nine children, and all of that is reflected in the verses after that. The last verse reflects her name and the types of maile that you find in the forest. When I wrote her that chant and it was presented to her for the first time in public in front of people, I made her stand up in front of thousands of strangers. Every time she would come to a performance, I would grab an opportunity to make her stand in front of thousands of people. And she hated it. But I wanted people to see, through example, that this is what you do, traditionally, to honor somebody. You write them a mele. And you do it in front of people. That’s the power of chants and songs. It doesn’t have power until you actually put it out of your mouth, into the air and into the ears of the listener. That’s where it completes its journey. If it’s just on paper or just in your head, it has no power. And so doing this in front of thousands of strangers was important.“MAUNALEO” from Melelana (1999)

I was still living in Wailuku. According to the writings of Inez Ashdown, who was Maui County’s historian emeritus [at Bailey House Museum], the two mountains that make up both sides of [nearby] ‘Iao Valley [are] Maunaleo and Maunakāne. I really liked the term Maunaleo (which means “the mountain’s voice”). I threw down some lines for Puakea and I said, “This is the tune. I’m missing a few lines in here, and I can’t make it work rhythmically.” I told him that the imagery that I had [in the words] was my mother. That this mountain is there. It stands like a sentinel. And no matter what’s come its way—fire, flood, storms—it’s still there. My mother is like that. In my immediate family she’s the rock and the scary one. Puakea came back and filled in some of the blanks. We adjusted some of the rhythm and some of the imagery. Like the song version of “He Lei No Kamaile” for my grandmother, [“Maunaleo”] wasn’t born right away. We had to sit and intellectually and culturally look at the imagery and say, “This is what we want to say,” and ask, “What if we use this word instead of that word?” There was a lot of bandying about.

I was still living in Wailuku. According to the writings of Inez Ashdown, who was Maui County’s historian emeritus [at Bailey House Museum], the two mountains that make up both sides of [nearby] ‘Iao Valley [are] Maunaleo and Maunakāne. I really liked the term Maunaleo (which means “the mountain’s voice”). I threw down some lines for Puakea and I said, “This is the tune. I’m missing a few lines in here, and I can’t make it work rhythmically.” I told him that the imagery that I had [in the words] was my mother. That this mountain is there. It stands like a sentinel. And no matter what’s come its way—fire, flood, storms—it’s still there. My mother is like that. In my immediate family she’s the rock and the scary one. Puakea came back and filled in some of the blanks. We adjusted some of the rhythm and some of the imagery. Like the song version of “He Lei No Kamaile” for my grandmother, [“Maunaleo”] wasn’t born right away. We had to sit and intellectually and culturally look at the imagery and say, “This is what we want to say,” and ask, “What if we use this word instead of that word?” There was a lot of bandying about.“MELE A KA PU‘UWAI” from Melelana (1999)

The writer of this song, ‘Iliahi Paredes, is a kumu hula. He was actually dancing for me, for a while, for the concerts. His future wife was one of our students, one of our solo dancers. And he wanted me to listen to something he wrote. He gave me a cassette of him singing the song, I listened to it and I loved it. I liked the timbre. I liked the thought process. He’d written the song as a going-away gift to one of his professors. I like showing people that you should write songs for people that you love and respect. This is a love song, but a different kind. When I started to sing it, it really fit into my tone and into my voice. To this day, it’s one of my favorite songs to sing. Because it’s easy, I don’t have to struggle [laughs]. The three biggest reasons why I decided to put it onto the album [were] I liked it, it felt good and [‘Iliahi] was fulfilling a cultural directive and doing it in a really, really good way. And he’s really talented.“KA NOHONA PILI KAI” from Ke‘alaokamaile (2003)

The song is about my grandmother’s house in Pā‘ia. It’s one of those old plantation-style homes. It’s right on the beach, which is unusual [for the area] nowadays. The house actually belonged to her aunty. My grandmother had been adopted into that family [but was] related by blood. She grew up here on Maui, but her roots are in Kohala. Her sisters and brothers were all raised in Kohala. The house became central for our entire family. Summertime we would have huge family gatherings. Tents everywhere. Fishing every day. Swimming every day. And music. When [her] aunty died, my grandmother moved into the house and lived there until she died. My mother’s sister continued to live there and we would go often. But, after a year, my aunty decided that she didn’t want to live there anymore. That was like a second death to us, because that hale (house) was our connection. It was our grounding. So I decided to write about all of the things I heard, saw and felt. The coconut trees—there’s a certain kind of sound that occurs. The sea spray. The sound of the ti leaves in the wind right outside the windows, because the windows were low. I wanted to document in song and imagery all of the stuff that me and the older cousins remembered. Some of the generation below us didn’t know my grandmother or had never met her. And it was important for me to do [the song] as a record, first and foremost, for the family. The house is still in the family. The energy is a little bit different, because it’s a different branch. We still have family gatherings, but not as many as before. And I sometimes take my hālau there so they can experience what I’ve experienced. A lot of the hālau chants that we do talk about that house. There’s nothing quite like using the environment as a teaching tool, especially when it comes to chant. I make them walk the yard and listen. I make them go down to the ocean and feel the temperature because the water and sand is different from the rest of the island. Hitting all of their senses and utilizing chants from this album, or chants within hālau that nobody else knows except hālau, is important.

The song is about my grandmother’s house in Pā‘ia. It’s one of those old plantation-style homes. It’s right on the beach, which is unusual [for the area] nowadays. The house actually belonged to her aunty. My grandmother had been adopted into that family [but was] related by blood. She grew up here on Maui, but her roots are in Kohala. Her sisters and brothers were all raised in Kohala. The house became central for our entire family. Summertime we would have huge family gatherings. Tents everywhere. Fishing every day. Swimming every day. And music. When [her] aunty died, my grandmother moved into the house and lived there until she died. My mother’s sister continued to live there and we would go often. But, after a year, my aunty decided that she didn’t want to live there anymore. That was like a second death to us, because that hale (house) was our connection. It was our grounding. So I decided to write about all of the things I heard, saw and felt. The coconut trees—there’s a certain kind of sound that occurs. The sea spray. The sound of the ti leaves in the wind right outside the windows, because the windows were low. I wanted to document in song and imagery all of the stuff that me and the older cousins remembered. Some of the generation below us didn’t know my grandmother or had never met her. And it was important for me to do [the song] as a record, first and foremost, for the family. The house is still in the family. The energy is a little bit different, because it’s a different branch. We still have family gatherings, but not as many as before. And I sometimes take my hālau there so they can experience what I’ve experienced. A lot of the hālau chants that we do talk about that house. There’s nothing quite like using the environment as a teaching tool, especially when it comes to chant. I make them walk the yard and listen. I make them go down to the ocean and feel the temperature because the water and sand is different from the rest of the island. Hitting all of their senses and utilizing chants from this album, or chants within hālau that nobody else knows except hālau, is important.“NĀ ‘ONO O KA ‘ĀINA” from Ke‘alaokamaile (2003)

I’m not quite sure who wrote it, though some attribute this composition to Abraham Kaulia, but [this song] on the surface talks about fishing [and] about the different things of the sea. My grandmother and her female cousins were extraordinary shoreline gatherers. My grandmother raised nine kids pretty much by herself. My grandfather was always away. He worked on Wake Island and traveled a lot. So my grandmother was basically the head of the household. Any way she could supplement the family was done, and fishing was one of them. She used to go pick ‘opihi (limpets). She would make ‘opihi bags out of 50-pound rice bags and would fashion them in a way that you could tie it around your waist and it hung right in front. The bags had a lip so you didn’t have to keep opening it to put in ‘opihi. I remember her and my aunties going out at daybreak and coming back three, four or five hours later with every 50-pound bag filled with ‘opihi. They were just amazing providers. Even up until my 20s, when I was living with her and going to school, my grandmother always provided. And we would still go fishing! She wouldn’t go pick [‘opihi] as much anymore, but, even in her 50s and 60s we would go out together. She’d make me go first, and then she’d follow behind to catch all of the stuff I missed. I would turn around and look and her bag was way more full than mine. This song is really just an ode to her skills, and to the skills of the women in our family.“HE LEI NO ‘AULANI” from ‘Aulani: Music of the Maka‘ala (2011) and Kawaiokalena (2014)

I was commissioned to write this song. I had never been commissioned in my life, for anything, though others had approached me before. I don’t play well in the sandbox with other people. I just don’t. So when Disney approached me [to write a song for its ‘Aulani Resort & Spa project on O‘ahu] it just struck me the wrong way. I thought, “One hotel? I no like write one song for one hotel.” They [said] they were really going to focus on Hawaiian culture. And I was, like, “Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. Sure.” I just wasn’t into it. They kept approaching me. And I kept saying no. My good friend, Maile Meyer, who owns [O‘ahu retailer] Nā Mea Hawai‘i, was the very final contact. And, she said, “Just hear them out. I’ll pick you up at the airport and we’ll go take you eat.” And, food, that goes far for me [laughs]. So I said, “All right. OK. I’ll do it for you.” So she picked me up and I met up with some of them. And instead of going to the property we went to Nānākuli Elementary School’s May Day program, which they’d given assistance so the kids could have a really fabulous May Day. And I was kind of, like, “OK, well maybe these guys are all right.” Then we went to the property. They sat me down and showed me all the plans. The architecture. The thought process. And I was kind of floored. Yeah, there was going to be Mickey Mouse and all of the characters. But the approach and what they were thinking and who they were hiring and all of the different Hawai‘i artists and artisans—some 30 or 40 that they were putting on retainer and just paying them—to me, was kind of impressive. And so I said, “OK. I’ll make my attempt. I’ll try it. But, you know, if you don’t like it, then you’re just gonna have to deal with it.” They wanted four songs. One for the place, and several that spoke more broadly of Hawaiian things. What those Hawaiian things were was up to me. I approached this particular song with the thought process of treating the hotel as a person. A person that is welcoming, that opens themselves up to people that come. And then, what are the places [in the area] that you can see? What makes this whole place famous? Basically, all four songs that I did, separately, started with “He Lei No ‘Aulani” as the epicenter. And with each successive song I moved further and further out from the epicenter [to encompass other districts of O‘ahu and the other Hawaiian Islands].“KAWAIOKALENA” from Kawaiokalena (2014)

This is my first song for the area I live in now [Pi‘iholo]. I think the song came first, before we even thought about the album. That’s when everything began to click. On the surface, it was about the place. But, in the chant I wrote for [Puna’s] 50th birthday, I gave him a new name, another name: Kawaiokalena. Kalena is the name of a series of ponds right down the street from here. They were famous in ancient times for whenever ali‘i (royalty) would come from other islands. When they traveled on Maui, they would inevitably stop there. So those are the royal ponds. There’s a small heiau (temple) next to one of the ponds, which tells you of its importance, culturally. When I gave [Puna] his name and his chant, I called it “the water of Kalena” [the English translation of kawaiokalena].” Just like Kawaipunahele. To me, it’s a water name. It also fit as a bookend. Everything [for the album] came very quickly after that. And so, really, this song and the chant talk about how we were on the ridge here and how the clouds nestled. Sometimes you can’t even see out this window. You’re in the thick of clouds. They roll in. It’s weird and kind of scary, actually. And if you open up all the windows it comes in. It’s very, very elemental up here. And so [the song] talks about this place. What I hope to do, as it has been with a lot of songs and chants and stuff, is to reintroduce people to a place again. A lot of my songs on the first albums—through turns of phrase, through poetry, through chant—reintroduced people to Wailuku and reminded them of all the things that made Wailuku famous. I hope some of what’s on this album does the same thing for the Pi‘iholo area.

This is my first song for the area I live in now [Pi‘iholo]. I think the song came first, before we even thought about the album. That’s when everything began to click. On the surface, it was about the place. But, in the chant I wrote for [Puna’s] 50th birthday, I gave him a new name, another name: Kawaiokalena. Kalena is the name of a series of ponds right down the street from here. They were famous in ancient times for whenever ali‘i (royalty) would come from other islands. When they traveled on Maui, they would inevitably stop there. So those are the royal ponds. There’s a small heiau (temple) next to one of the ponds, which tells you of its importance, culturally. When I gave [Puna] his name and his chant, I called it “the water of Kalena” [the English translation of kawaiokalena].” Just like Kawaipunahele. To me, it’s a water name. It also fit as a bookend. Everything [for the album] came very quickly after that. And so, really, this song and the chant talk about how we were on the ridge here and how the clouds nestled. Sometimes you can’t even see out this window. You’re in the thick of clouds. They roll in. It’s weird and kind of scary, actually. And if you open up all the windows it comes in. It’s very, very elemental up here. And so [the song] talks about this place. What I hope to do, as it has been with a lot of songs and chants and stuff, is to reintroduce people to a place again. A lot of my songs on the first albums—through turns of phrase, through poetry, through chant—reintroduced people to Wailuku and reminded them of all the things that made Wailuku famous. I hope some of what’s on this album does the same thing for the Pi‘iholo area.